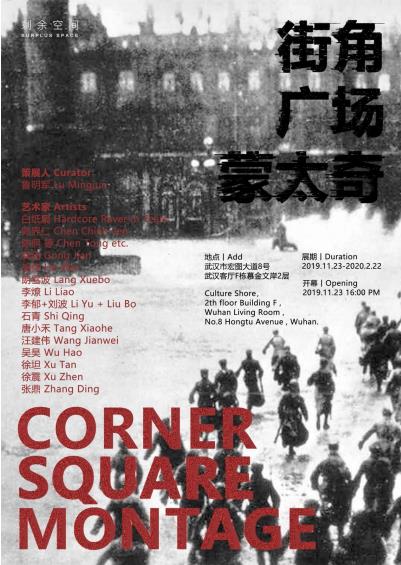

街角广场蒙太奇

参展艺术家:白纸扇,陈界仁,陈侗,龚剑,胡伟,朗雪波,李燎,李郁+刘波,石青,唐小禾,汪建伟,吴昊,徐坦,徐震,张鼎

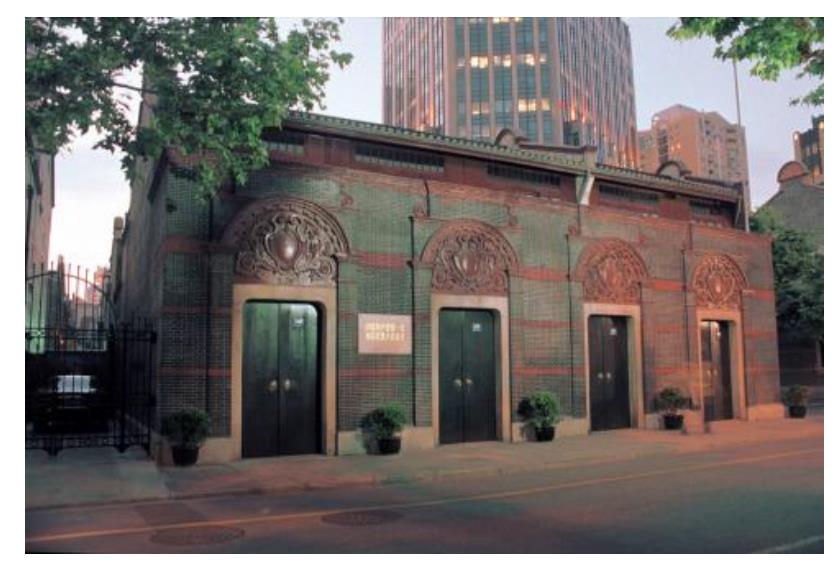

展览地址:武汉市宏图大道 8 号武汉客厅 F 栋慕金文岸 2 层

2019.11.13-2020.2.22

1976 年,美国艺术评论家、艺术史家安妮特·麦克尔森(Annette Michelson)和罗萨琳·克劳斯(Rosalind Krauss)创办了《十月》杂志。杂志的名字取自爱森斯坦 1927 年为纪念“十月革命”10 周年执导的同名电影《十 月》,这也是托洛茨基被驱逐出境的一年。

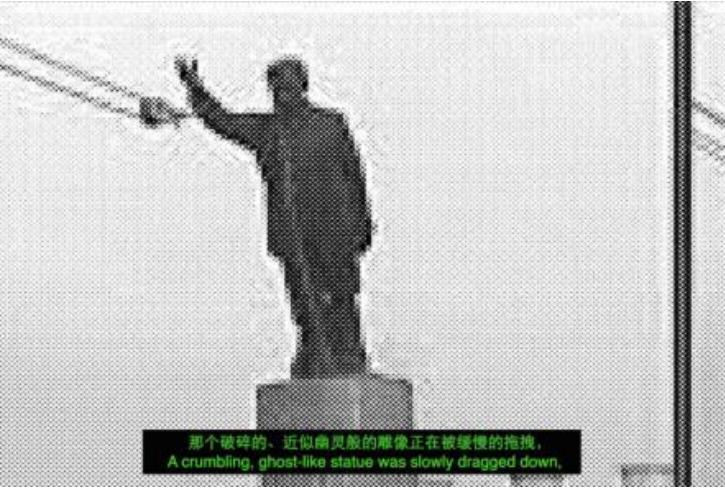

爱森斯坦是“二月革命”和“十月革命”这两场革命的亲历者,影片悉数了他对于这两场革命的体认和感知。在一篇题为《电影形式的辩证观》的文章中,爱森斯坦说一切新事物均产生于对立矛盾的斗争之中,“十月革命”是改变世界历史、创生新制度的时代拐点,蒙太奇能生动地揭示革命的斗争性。“二月革命”与“十月革命”有着本质的不同,前者为资产阶级革命,后者则是无产阶级的,而“辩证蒙太奇”(dialectic montage)在银幕上所表现的正是这两者之间的断裂。

爱森斯坦的《十月》是苏联无声电影的集大成者,它不仅开创了一种新的艺术范式,其本身也可以被视为一种政治行动。正是这一集革命实践、理论探索与艺术创新为一体的时刻成为麦克尔森和克劳斯思考和行动的起点,对于他们而言,半个多世纪前发生在苏俄的这场艺术革命辐射至文学、绘画、建筑、电影各个领域,而孕育这一艺术革命和历史运动的则是内战、派系纷争和经济危机。在《十月》杂志的发刊辞中,两位编辑明确她们的目的并非让革命的神话或圣训不朽,也无意分享这种自我验证的悲情,而是希望重新探讨此时她们自身文化中几种艺术之间的关系,并以此为基础,在这个重要的历史关头重新讨论它们的意义和作用。

事实上,在《十月》创刊之前,麦克尔森在《艺术论坛》(1973 年第 1 期)已经发表过一篇有关苏联前卫电影的论文《暗箱,明箱》。文章主要探讨了爱森斯坦和斯坦·布拉哈格(Stan Brakhage)两位不同时期导演的作品,尤其着重分析了爱森斯坦《十月》的电影语言。麦克尔森指出,对于爱森斯坦来说,电影就是哲学功能的承继,他将审美原则具体化为一种认识论,并最终导向一种伦理学,因此,“蒙太奇思维无法与整体性思想分离”。《十月》就是不断回述“电影形式”(Film Form)和“电影意义”(Film Sense)的思维范例。爱森斯坦对自身能动的、深刻的介入意识——将自身归入革命的历史进程——令我们认识到他的作品实为历史转换进程中的某种矢量。这里,麦克尔森已经明确了爱森斯坦《十月》的电影语言或“史诗风格”与革命政治之间的一体关系。而对于麦克尔森来说,电影只是其中一部分,她在文中也提到爱森斯坦当时受到了当时诗歌、绘画与戏剧的滋养,这些艺术都沿着俄国“十月革命”前后的复杂路径相继发生,从未来主义起贯穿立体主义直到构成主义。通过对塔特林与罗德琴柯的认识,以及他们如何理解立体主义,我们才能对爱森斯坦有更加深入的理解。三年后,《十月》1976 年第 2 期刊发了爱森斯坦于 1927-28 年间关于《资本论》这部电影的笔记,以及麦克尔森的介绍和评论。麦克尔森在评论中也提到了《十月》,文中写道,“《十月》是爱森斯坦在走向彻底的艺术电影方面最精细、最复杂的一次努力。……它通过改变事件及其周围叙述结构的时间流,……吸引新的注意力并引起对空间和时间关系的推论。”在这里,“蒙太奇的力量存在于‘原始’的事实上,理想的形象不是固定的或现成的,而是产生的,它聚集在观众的感知中”。时至今日,《十月》杂志封面的右上角依然标注着“艺术”“理论”“批评”“政治”四个关键词,作为刊物的基本定位和价值理念。而且从一开始,他们就明确了《十月》是反商业、反学院、反体制的。这也是其与此时已经被商业化了的抽象表现主义和形式主义的区别所在。但并非巧合的是,20 世纪初期的革命前卫构成了他们共同的叙事起点。《十月》的发刊词中提到了《党派评论》这本带有托洛茨基主义色彩的左翼刊物,两位编辑并未否认《党派评论》的政治性,只是觉得它越来越“无视艺术和批评方面的创新”,甚至“鼓励了知识界中新的庸俗主义的发展”。不容忽视的是,《党派评论》也是格林伯格早期主要的理论阵地。上世纪 40 年代初,他曾担任杂志编辑数年,而且,其早期最重要的评论文章《前卫与媚俗》(1939)便发表在《党派评论》上。文中,格林伯格旗帜鲜明地反对媚俗的学院主义、商业主义和社会主义现实主义,对他来说,真正代表前卫的就是抽象绘画。这里的抽象表面指的是形式主义绘画,但实际上,它喻示的是 1917 年“十月革命”所开启的整个前卫艺术运动,包括文学界的马雅可夫斯基和 LEF 小组,绘画中的形式主义和构成主义流派,电影界中的爱森斯坦、普多夫金、多夫申科,戏剧界中的泰罗夫和麦耶霍尔德,等等。而前卫艺术运动的精神领袖正是托洛茨基主义。关于这一背景,皮力曾经做过非常清晰的梳理:1924 年,列宁逝世后,斯大林掌握了苏联的最高权力。1927 年,托洛茨基被斯大林开除出党并被驱逐四处流亡。

1928 年,为了肃清托洛茨基的影响,斯大林加强了对于第三国际的控制,斯大林主义逐渐取代了托洛茨基主义,这也引起了很多曾经支持十月革命的欧洲进步知识分子的警觉。同年,打着左翼社会主义旗号登上政治舞台的墨索里尼在意大利终止了议会,取消所有政治团体并镇压进步的知识分子和共产党,墨索里尼的崛起让进步知识分子看到了欧洲的法西斯主义危险,整个 20 年代末到 30 年代中期,知识分子还试图将消灭法西斯主义的希望寄托在斯大林身上,即使在 1933 年希特勒上台之后,他们也不曾放弃希望。然而,1939 年 8 月,斯大林和希特勒签署了互不侵犯条例,并且秘密瓜分了波兰。《苏德互不侵犯条约》导致欧洲的进步知识分子对于苏维埃和斯大林主义的理想彻底幻灭,在他们看来这是法西斯主义和斯大林主义的合流。当他们联想到苏联对于构成主义艺术家的放逐,觉得斯大林主义几乎就

是法西斯主义的同义词。于是,现代主义和共产主义的蜜月期也就在这一刻划上了句号。

这一年,格林伯格发表了《前卫与媚俗》一文。这应该不是巧合。格林伯格虽然批判了社会主义现实主义和法西斯主义艺术,但并没有放弃革命政治和现代主义。也就是说,托洛茨基主义是他理论的底色。文章的最后,他说:“如今,我们不再将一种新文化寄希望于社会主义——旦我们真的拥有了社会主义,这种新文化似乎必然会出现。如今,我们面向社会主义,只是由于它尚有可能保存我们现在所拥有的活的文化。”这里的社会主义不是斯大林的社会主义,而是托洛茨基的社会主义。约 20 年后,在一篇题为《纽约绘画刚刚过去》(1957)文章的一个脚注中,格林伯格这样写道:“尽管那些年的艺术都讲究政治,但也并非全然如此;将来的某一天,人们也许应该说明多少出于‘托洛茨基主义’的‘反斯大林主义’,是如何转化为‘为艺术而艺术’,从而英雄般地为随后到来的东西清理了道路的。”这已然明确了他跟托洛茨基主义的关系,而其之所以被置于脚注或许就是为了“掩人耳目”,毕竟,此时整个美国尚未走出麦卡锡肃清的阴影。

前面提到,1927 年托洛茨基被驱逐出境,开始了流亡生涯。是年,爱森斯坦完成了纪念“十月革命”10 周年的影片《十月》。值得一提的是,1924 年,托洛茨基曾发表一篇重要的长文,题为《十月的教训》。文中对 1917 年“十月革命”(包括“二月革命”)以来的“无产阶级和农民的民主专政”“七月事变,科尔尼洛夫叛乱”“苏维埃的‘合法性’”等问题进行了系统的梳理和检讨,在此基础上,重申了共产国际“布尔什维克化”的必要性——这是一项无可争辩、确定无疑的任务。他说:“布尔什维克不仅仅是学说,而是无产阶级革命的革命教育体系。……‘这就是黑格尔,这就是这本书上的智慧,这也就是全部哲学的意义!……’”托洛茨基最后提到了黑格尔,巧合的是,爱森斯坦所谓的“辩证蒙太奇”即“相反的动作”和“规律的统一”与黑格尔的辩证法是一致的,即都是通过“正——反——合”进入新的“正——反——合”,以此类推,矛盾在不断冲突中螺旋上升、发展。且不知爱森斯坦的《十月》是否直接来自托洛茨基的这篇长文,但二者之间的确隐伏着这一内在的关联。半个世纪后,克劳斯和麦克尔森选择它作为创办《十月》杂志的动因之一。“十月革命”、爱森斯坦以及(早期)格林伯格共同构成了其行动的起点。此时,美苏正处于冷战阶段,但显然,《十月》并非站在冷战的任何一方,其真正认同的还是第四国际:“托洛茨基主义”。尽管格林伯格也曾提到现代主义实践的一面,但自 1940 年代末开始到 60 年代前后,他几乎很少提到现代主义何以作为革命政治运动,也看不到对于资产阶级和庸俗文化的批判。不可忽视的一个重要原因是 1950-54 年初麦卡锡主义的清洗,某种意义上,正是麦卡锡肃清迫使格林伯格放弃了革命政治,而只是致力于建构一套“封闭”的形式主义话语,进而演变成一套单极化的霸权叙事。然而,这套话语很快便与崛起的艺术市场合谋,并多少附和了占据主流、全球扩张的新自由主义意识形态。也正是在此期间,各种反形式主义霸权的声音伴随着民权运动、反战运动和反文化运动的浪潮此起彼伏,特别是观念艺术及其“去物质化”运动的兴起,最终导致形式主义的撤退。艺术界期待一场新的革命,而《十月》无疑是这场新的革命阵营的一部分。诚如格林伯格在《前卫与庸俗》一文中所说的:“哪里有前卫,一般我们也就能在哪里发现后卫。”这句话也可以倒过来说:哪里有后卫,哪里就有前卫。2018 年 9 月,麦克尔森因病去世,享年 97 岁。年近耄耋的克劳斯依然精神矍铄。而《十月》业已走过了 40 余年的历史。尽管今天的艺术评论、艺术媒体乃至整个艺术生态已不同往昔,但《十月》依然卓尔不群。它不仅一场艺术批评和艺术认知的革命,本身也是一场政治运动。如果说这是《十月》杂志诞生的意义,那么今天的问题是,我们能否寻得一个同样或相似的——亦或说我们能否回到这样一个——行动的起点?也许,我们还须重申 90 年前托洛茨基的追

问:“什么是不断革命?”

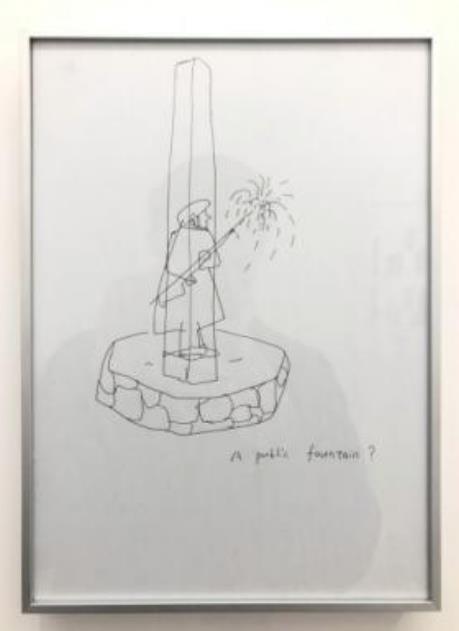

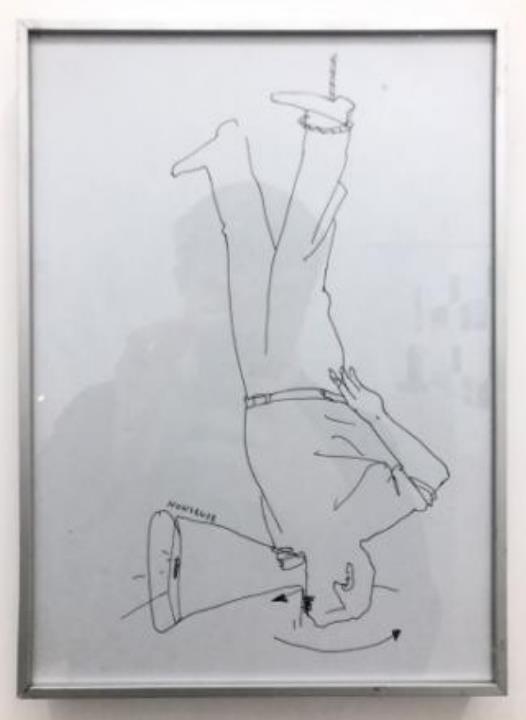

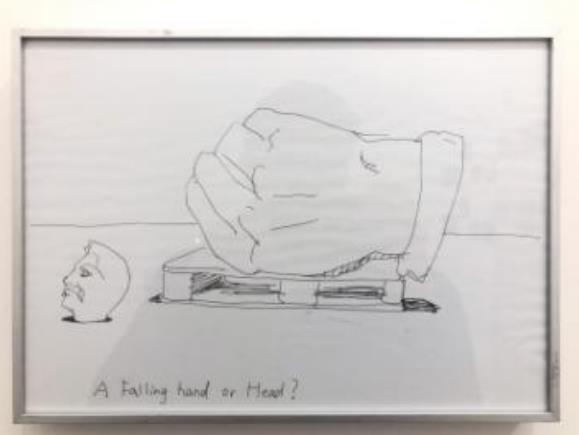

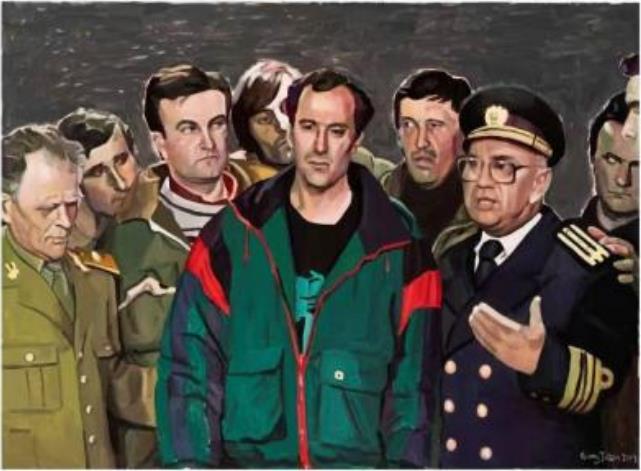

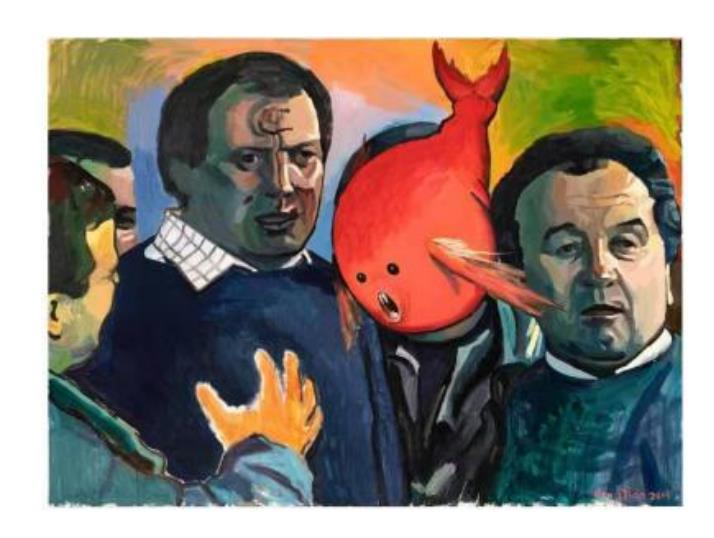

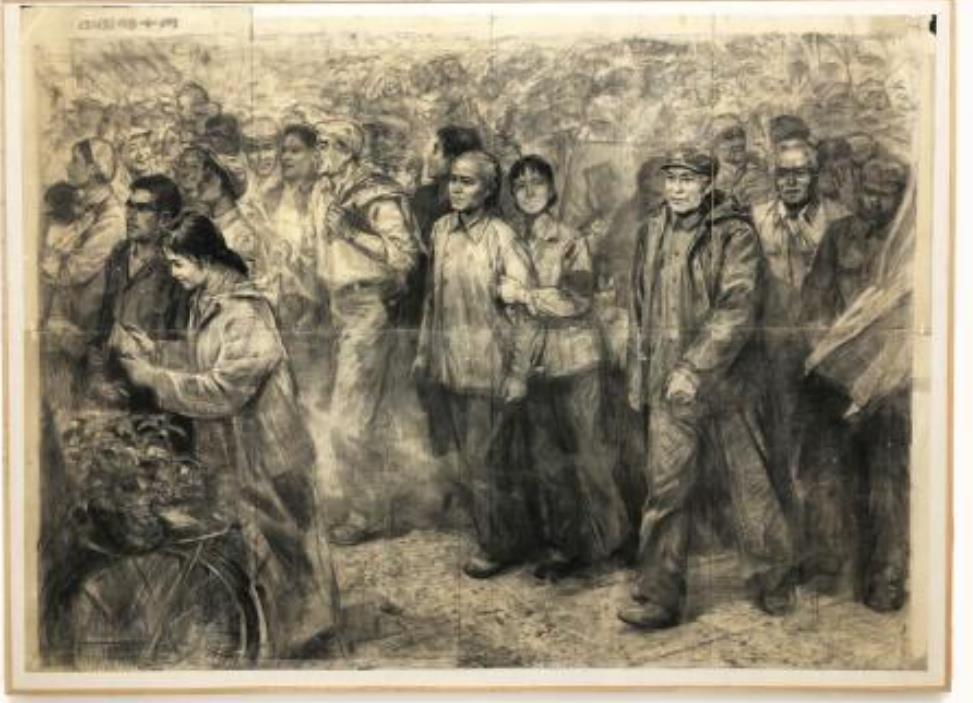

在今天这一新的历史关头,展览《街角,广场与蒙太奇》希望再次回到这一前卫时刻。展览由剩余空间艺术总监鲁明军策划,特别邀请了唐小禾、汪建伟、陈界仁、徐震、张鼎、石青、龚剑、李郁+刘波、朗雪波、李燎、胡伟、吴昊等 10 余位艺术家参展,希望通过他们不同时期、不同媒介、语言和风格作品之间的相互碰撞,激荡出一种新的蒙太奇和政治力。

值此麦克尔森逝世一周年之际,谨以此展献给这位不凡的知识分子和革命者!

展览现场

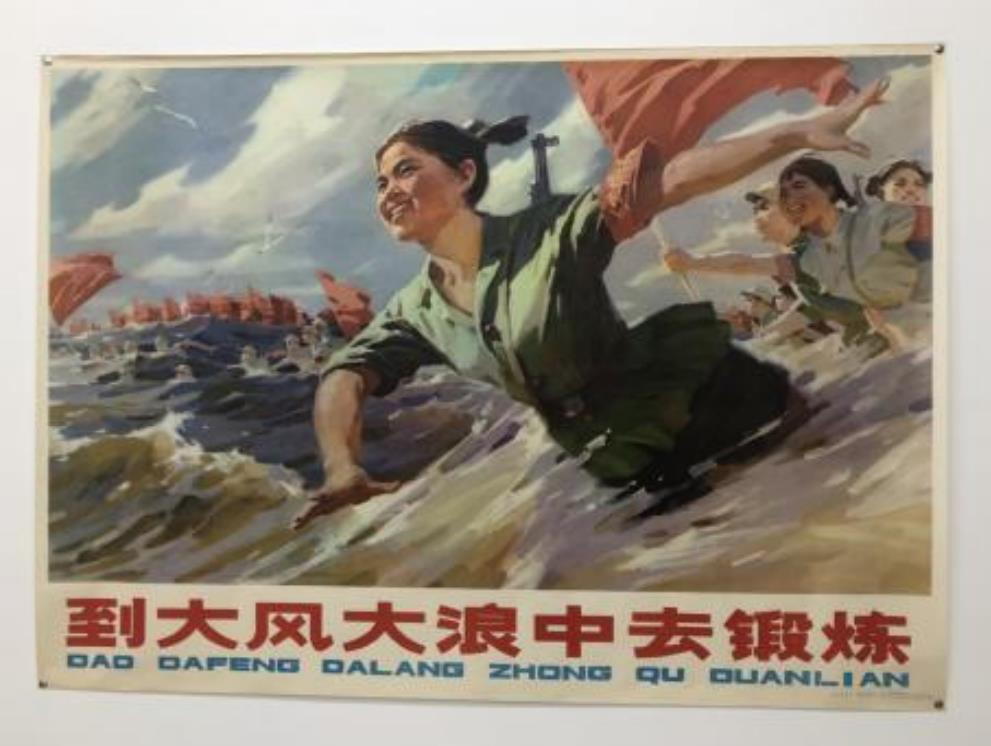

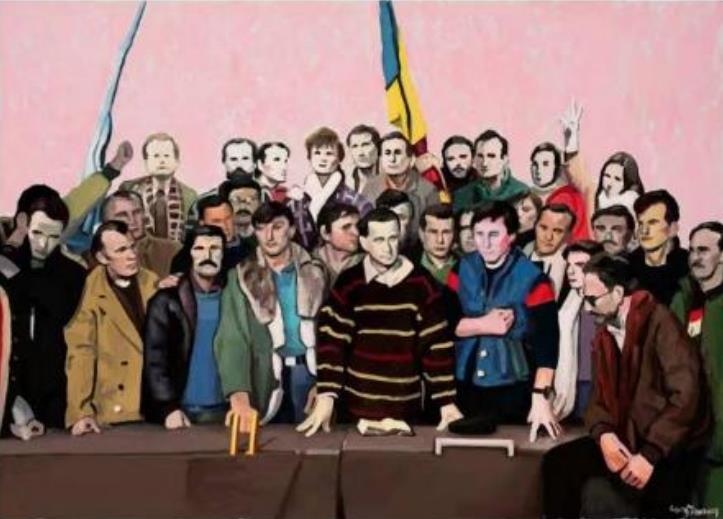

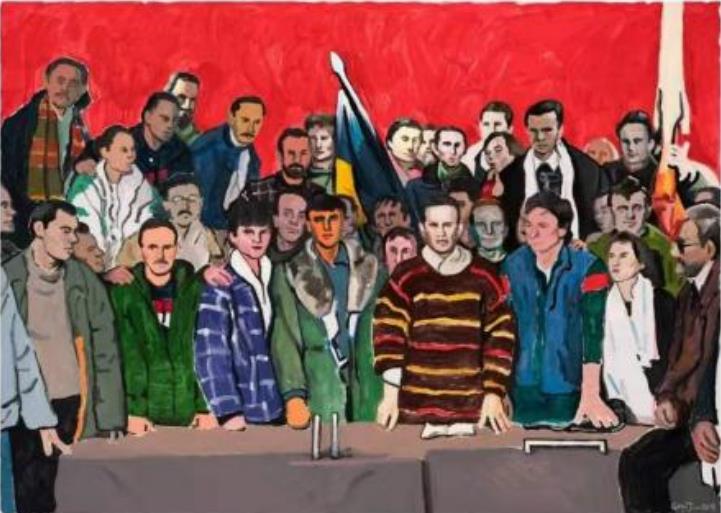

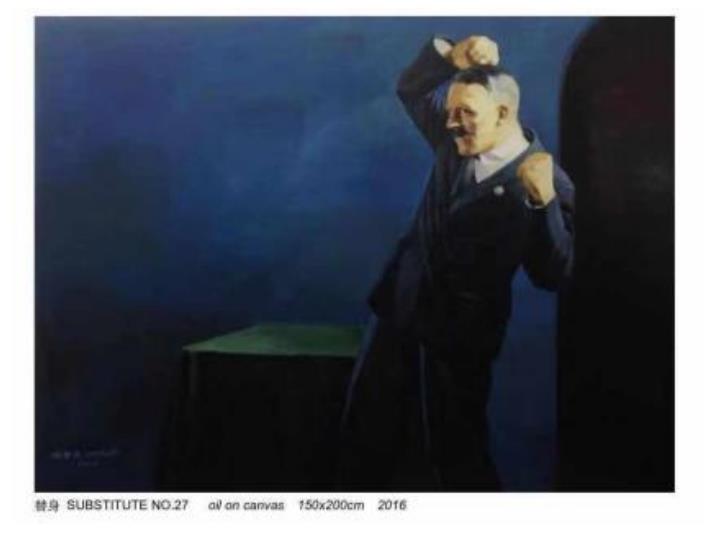

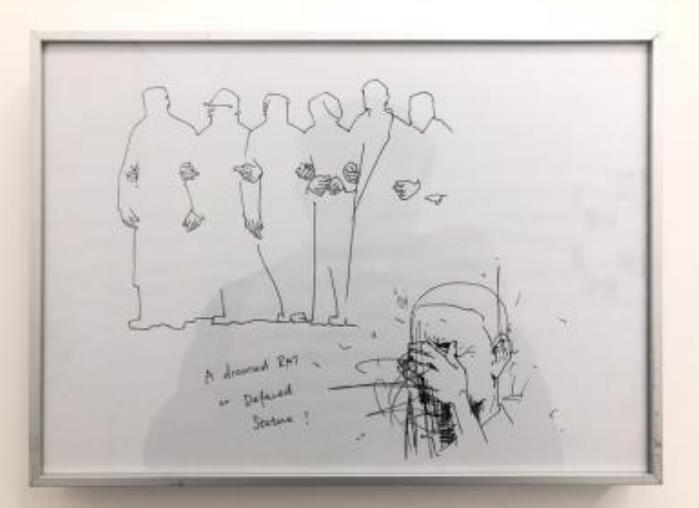

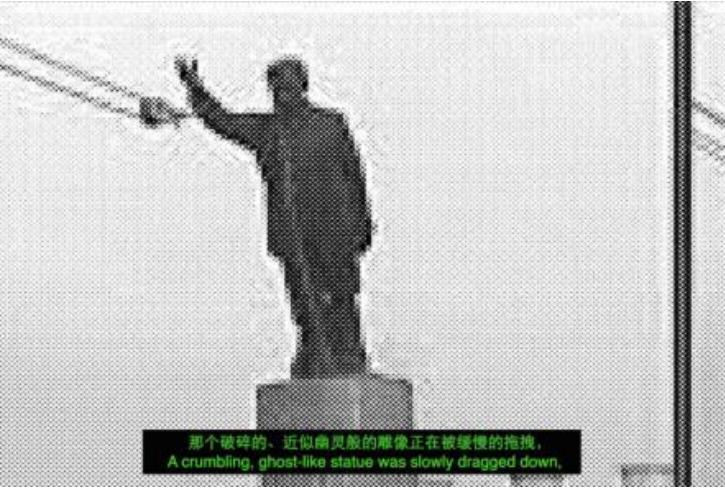

展出作品